|

Adnexal Masses |

Adnexal masses may be encountered during a routine examination of an asymptomatic patient. They may be found while evaluating a patient with pain, bleeding, or other troublesome symptom. Most of these masses will be benign and largely self-resolving, while a few will prove dangerous or life-threatening. The challenge, of course, is to determine which is which.

|

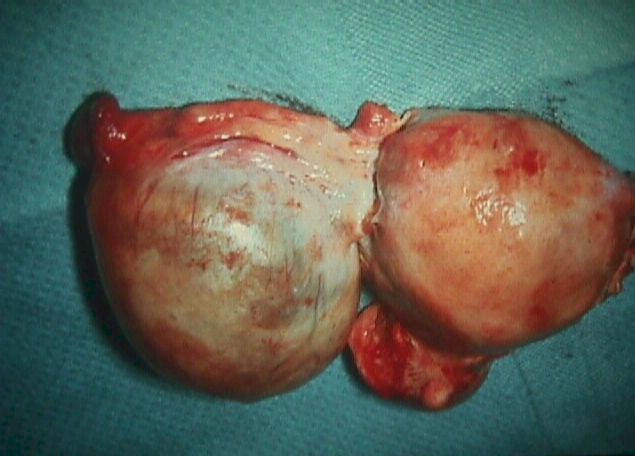

Simple cyst of the ovary, in a hysterectomy specimen (cyst on your left, uterus on your right) |

Simple Ovarian Cysts

An ovarian cyst is a fluid-filled sac arising from the ovary.

Ovarian cysts can be broadly categorized as having two

origins: physiologic cysts as a consequence of ovulation, and neoplastic

cysts. Of the two, ovulation-related cysts are by far the more common.

Ovarian cysts can be broadly categorized as having two

origins: physiologic cysts as a consequence of ovulation, and neoplastic

cysts. Of the two, ovulation-related cysts are by far the more common.

Functional cysts are common and generally cause no trouble. Each time a woman ovulates, she forms a small ovarian cyst (3.0 cm in diameter or less). Depending on where she is in her menstrual cycle, you may find such a small ovarian follicular cyst. Large cysts (>7.0 cm) are less common and should be followed clinically or with ultrasound.

Occasionally, simple ovarian cysts may cause a problem by:

- Delaying menstruation

- Rupturing

- Twisting

- Causing pain

95% of ovarian cysts disappear spontaneously, usually after the next menstrual flow. Those that remain and those causing problems are often removed surgically.

|

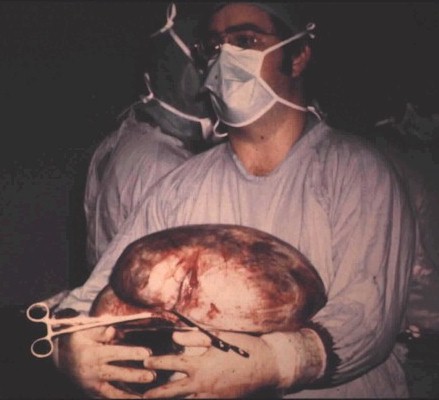

70 pound mucinous cystadenoma (benign) |

Unruptured Ovarian Cyst

While most of these have no symptoms, they can cause pain, particularly

with strenuous exercise or intercourse. Treatment is symptomatic with rest for those with

significant pain. The cyst usually ruptures within a month.

Once ruptured, symptoms will gradually subside and no further treatment is necessary. If it doesn't rupture spontaneously, surgery is sometimes performed to remove it. This will relieve the symptoms and prevent torsion.

Ruptured Ovarian Cyst

This is an ovarian cyst that has ruptured and spilled its' contents into

the abdominal cavity.

If the cyst is small, its' rupture usually occurs unnoticed. If large, or if there is associated bleeding from the torn edges of the cyst, then cyst rupture can be accompanied by pain. The pain is initially one-sided and then spreads to the entire pelvis. If there is a large enough spill of fluid or blood, the patient will complain of right shoulder pain.

Symptoms should resolve with rest alone. Rarely, surgery is necessary to stop continuing bleeding.

|

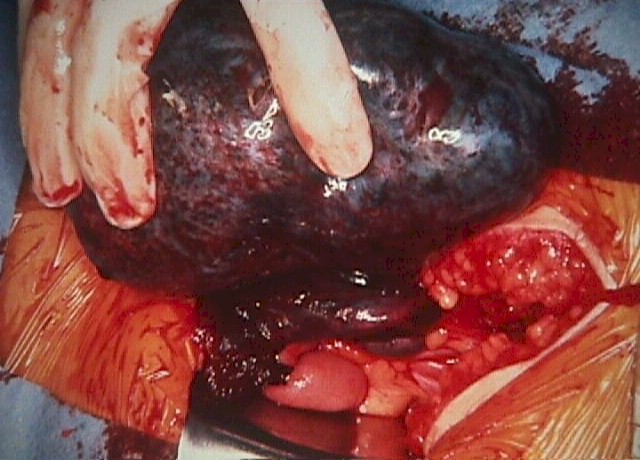

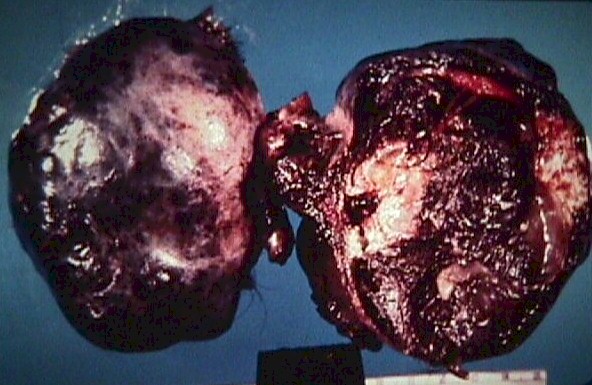

Torsioned Ovarian Cyst |

Torsioned Ovarian Cyst

A torsioned ovarian cyst occurs when the cyst twists on its' vascular

stalk, disrupting its' blood supply. The cyst and ovary (and often a portion of the

fallopian tube) die and necrose.

Patients with this problem complain of severe unilateral pain with signs of peritonitis (rebound tenderness, rigidity). This problem is often indistinguishable clinically from a pelvic abscess or appendicitis, although an ultrasound scan can be helpful.

Treatment is surgery to remove the necrotic adnexa. If surgery is unavailable, then bedrest, IV fluids and pain medication may result in a satisfactory, though prolonged, recovery. In this suboptimal, non-surgical setting, metabolic acidosis resulting from the tissue necrosis may be the most serious threat. Mortality rates from this condition (without surgery) are in the range of 20%.

Other surgical conditions which may resemble a twisted ovarian cyst (such as appendicitis or ectopic pregnancy) may not have a good outcome if surgery is delayed. For this reason, patients thought to have a torsioned ovarian cyst should be moved to a definitive care setting where surgery is available.

|

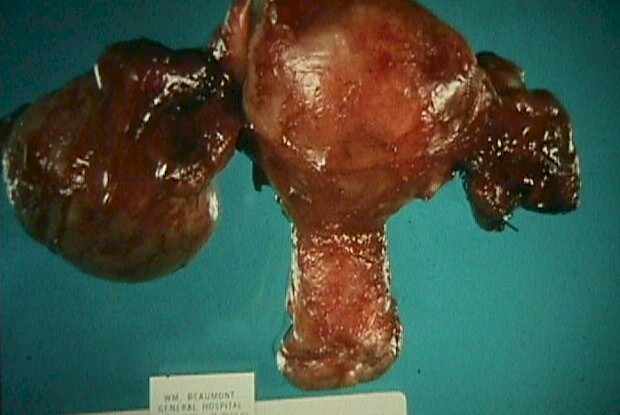

Endometrioma of Right Ovary |

Endometrioma

An endometrioma is a form of an ovarian cyst that results from ectopic

endometrial tissue being present in the ovary. During the normal cyclic

hormonal changes, this ectopic endometrium responds with proliferative

growth, decidualization, and then sloughing, accompanied by bleeding. As

the blood is trapped within the ovarian capsule or stroma, it gradually

accumulates, forming a chronic hematoma, known as an endometrioma. If

large enough, these masses can be found during an examination or

identified on ultrasound.

The most troublesome aspect of endometriomas from a diagnostic standpoint is that they can mimic any of the ovarian neoplasms. Classically, the endometriomas have a ground-glass, slightly speckled appearance on sonar, but may demonstrate both cystic and solid components.

Ovarian Neoplasms

Ovarian Neoplasms

Ovarian neoplasms vary in seriousness from annoying (not cancer), to

slowly growing, to aggressively invasive. They may be solid,

fluid-filled (serous or mucinous) or mixed (complex). Their clinical

significance may not be related to their microscopic appearance. Dermoid

tumors, rarely malignant, are most threatening because of their

tendency to twist on their vascular stalk, causing ovarian necrosis.

Ovarian neoplasms may be primarily cystic, solid, or mixed. Some are benign, some are malignant. Some produce enough hormone to cause symptoms for the patient. Some examples of these shown below.

| Primarily Cystic | Primarily Solid | Mixed |

|

|

|

|

Dermoid cyst with torsion and infarction |

Dermoid Tumor

These common neoplasms contain a variety of elements of dermal

origin, including teeth, hair, sebaceous glands, and hormone-producing

thyroid cells.

They are also called ovarian teratomas, are usually benign and occasionally malignant. Bilaterality is common.

They have several annoying features:

- They can rupture and spill their epithelial contents into the abdominal cavity where they may implant and grow, making later removal difficult if not impossible.

- They may produce enough thyroid hormone to produce frank thyrotoxicosis.

- They may twist on their vascular pedicles, causing necrosis, an acute abdomen, and the need for emergent surgical intervention.

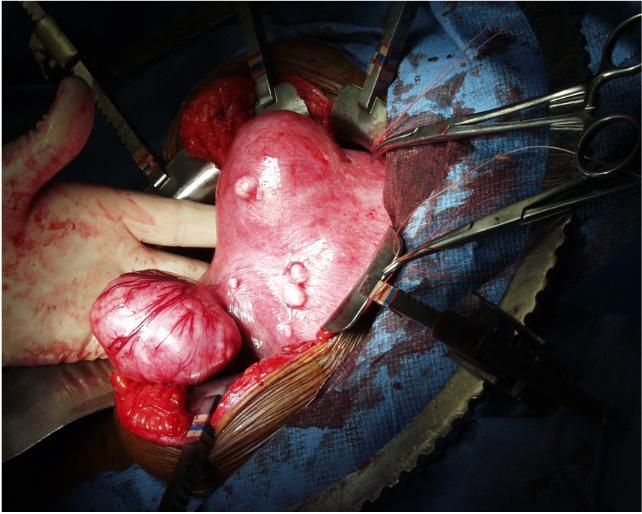

Uterine

Fibroid Tumors (Leiomyomas)

Uterine

Fibroid Tumors (Leiomyomas)

Typically, uterine fibroid tumors are easily identified within the

uterus, both by clinical exam, and by such imaging studies as diagnostic

ultrasound. Sometimes, uterine fibroids are growing in an area that

cannot be distinguished from the adnexa. In these cases, the fibroids

may appear to be a solid adnexal mass. Ultrasound is usually but not

always helpful in tracking the base of the fibroid back to the uterus.

Occasionally, it will only be through surgical intervention that the

source of this adnexal mass will become clear.

Read more about uterine fibroids

Ovarian Cancer

The life-time risk for a woman to develop ovarian cancer is about

1%, but varies with race, socioeconomic status, and continent. However,

there are other factors that may increase or decrease that risk.

- Taking oral contraceptive pills decreases the risk of developing ovarian cancer, particularly if the OCPs have been taken for a long time. The initial reduction of risk of about 40% increases with increasing use.

- Pregnancy decreases the risk of ovarian cancer. A single full-term pregnancy lowers the risk by about 40%, and each subsequent pregnancy decreases it somewhat more.

- Having a tubal ligation or hysterectomy (with preservation of the ovaries) decreases the risk of ovarian cancer by about 50%.

- Removal of one ovary does not change the risk of later development of ovarian cancer.

- Using fertility-enhancing medications to stimulate ovulation may increase the risk of ovarian cancer. This risk is relatively small and not all studies agree that the risk increases.

- A family history of breast or ovarian cancer increases the patient's risk of ovarian cancer.

- The presence of the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene increases the lifetime risk of developing epithelial cell ovarian cancer to about one in three.

- The incidence of ovarian cancer steadily increases with age, peaking in the mid-60s. Ovarian cancer among younger women is rare. Prior to age 30, the incidence is 5/100,000.

Detection

Ovarian cancer can be difficult to detect. Unlike uterine cancer (that tends

to cause visible bleeding at a relatively early stage), ovarian cancer usually

remains symptomless until fairly late in the disease process. Symptoms

associated with ovarian cancer include pelvic discomfort and bloating.

Unfortunately, these symptoms are so non-specific as to be nearly useless in

evaluating a patient for possible ovarian cancer. Further, by the time a patient

develops these symptoms, the ovarian cancer has frequently spread to distant

sites.

Blood tests are of limited value. Serum CA-125 increases in the presence of most ovarian epithelial cancers. Unfortunately, it also increases in the presence of anything that irritates the peritoneal surface, including infection, endometriosis, ovulation, and trauma. Further limiting its usefulness has been the observation that by the time the serum CA-125 levels increase in response to ovarian cancer, it is no longer in its early stages.

Transvaginal ultrasound scanning has been used, with some success, to identify ovarian cancer. Ultrasonic findings that can be suspicious for ovarian cancer include unusually large amounts of free fluid in the abdominal cavity, solid ovarian enlargement, mixed cystic and solid enlargement of the ovaries, and thick-walled or complex ovarian cysts. Like CA-125, diagnostic ultrasound has some limitations to its usefulness. By the time the macroscopic changes of ovarian cancer are detectable by ultrasound, most ovarian cancers are well beyond the early stage of the disease. Also, most abnormalities seen by ultrasound are not, in fact, cancer, but are benign findings that require no treatment. For these reasons, most ultrasound screening programs for early detection of ovarian cancer have been discontinued. The vast majority of the abnormalities found (and surgically removed) actually required no treatment, and the few cancers that were successfully identified and removed were far enough advanced that it remained doubtful that the ultrasonic detection of them made any difference.

That said, using CA-125 and ultrasound (and CT scanning or MR imaging) to evaluate an adnexal mass can be helpful. Simple ovarian cysts are virtually never malignant, and observing more complex masses over time can distinguish between the many that are benign (corpus luteum cysts, for example), and the few that are malignant and growing.

| Ultrasound findings that decrease the concern for malignancy | Ultrasound findings that increase the concern for malignancy |

|

|

Ovarian Cancer Management

Specific management of ovarian cancer hinges on the cell type (and grade),

the extent of spread (stage), and sometimes may be modified by particular

patient characteristics (such as a desire to preserve childbearing capacity).

The histologic evaluation requires a tissue specimen from the cancer that can be evaluated by the pathologist. For some ovarian cancer cell types, the histologic grade had prognostic significance (the more well-differentiated, the better). For other cell types, histologic grade has not been shown to have much of an independent prognostic value.

Staging of the cancer is usually accomplished at the time of surgery and takes into account the spread of the disease. Guidelines for staging come from the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO). Stages include:

- Stage I (Growth limited to the ovaries, and subdivided into Stage IA, IB, and IC, depending on the number of ovaries involved, presence or absence of ascites, tumor cells on the external surface of the ovaries or in peritoneal washings)

- Stage II (Growth beyond the ovaries, but limited to the pelvis. Stage II is further subdivided into IIA, IIB, and IIC, depending on the specific areas of extension, presence of ascites, and tumor cells in peritoneal washings)

- Stage III (Growth out of the pelvis, but still within the epithelial surfaces of the abdominal cavity. This is subdivided into IIIA, IIIB, and IIIC, depending on the location of the growth and its size.)

- Stage IV (Distant metastases outside the confines of the abdominal cavity or within the liver parenchyma).

The prognosis for early stage cancer of the ovary is generally good, the earlier the better. Unfortunately, not many Stage IA ovarian cancers are detected and treated. Most are of a more advanced stage where the prognosis is more guarded, the higher, the worse.

Surgical treatment options include local excision, TAH/BSO, and such debulking procedures as omentectomy and bowel resection. Even if the entire tumor cannot safely be removed surgically, reducing its bulk by at least 90% will often result in improved survival. Depending on the cell type, radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy can also be used with good results. Occasionally, sub-optimal surgical treatment will be accepted as a compromise to enable other worthy goals. For example, an early ovarian cancer might optimally be treated with TAH/BSO, but instead, a simple oophorectomy is performed to preserve the woman's childbearing capacity. In such a case, the woman must be prepared to accept the increased risk of treatment failure as the appropriate trade-off in retaining her capacity to have children.

|

Hydrosalpinx from PID |

Fallopian Tube Masses

Tubal ectopic pregnancy can present with an adnexal mass as either a primary or

incidental finding. These masses can arise in two ways. If the ectopic pregnancy

is large enough (and it must be quite large), then it may be found on physical

examination or ultrasound exam. Another commonly-found adnexal mass is the

corpus luteum frequently found on the opposite side of the ectopic pregnancy.

Ectopic pregnancy treatment options are many.

Pelvic inflammatory disease can sometimes lead to a fallopian tube abscess or a fluid-filled tube (hydrosalpinx). If large enough, this mass can be palpated on examination or seen on ultrasound. If asymptomatic, these masses are usually ignored. If they are causing significant symptoms, they are removed surgically.

Evaluation of the

patient with an adnexal mass

Evaluation of the

patient with an adnexal mass

The primary goal of this evaluation is to distinguish those patients with an

innocent, self-resolving mass from those who will need intervention to achieve

the best results.

Evaluation techniques that may prove useful include:

- Re-examine the patient after the next menstrual flow to see if the mass has disappeared.

- Exam under anesthesia if the normal exam is equivocal or difficult.

- Pregnancy test to rule out ectopic pregnancy or intrauterine pregnancy that may influence management choices.

- Have the patient use an enema to cleanse the lower bowel of stool and then re-examine the patient to see if the mass has disappeared.

- Pelvic ultrasound scan to identify the sonographic characteristics of the mass.

- Serum CA-125 level to see if the peritoneal surface is being irritated.

- CT scan (with contrast) of the abdomen and pelvis to evaluate out the possibility that the mass from of a non-gynecologic source, such as a pelvic kidney, diverticular abscess, or colon carcinoma.

- Culdocentesis or paracentesis of ascitic fluid for microscopic evaluation.

- Laparoscopy to look directly at the pelvic mass, with possible laparoscopic removal

- Laparotomy to explore the mass and remove it.